By

Pastor Stephen Feinstein

In today’s post, I will be

summarizing Francis Schaeffer’s discussion on mysticism as it affected music

and art. Recall that mysticism is the third level below the line of despair.

The line of despair refers to the rejection of the existence of absolutes, such

as truth. This way of thinking is the natural byproduct of atheism. If the universe

is not God’s universe, but instead it is random material happenings, then there

can be no absolutes. Truth would be relative, right and wrong would be concepts

of nonsense, and all existence would be without meaning and purpose. Many

people bought into this, but it proved impossible to live out. As humans made

in the image of God, we live according to absolutes, we cannot separate ourselves

from them, and we intrinsically know that everything has meaning and purpose.

We know things are not random. Our very lives depend on the universe being

stable and predictable rather than random and chaotic. So those who still chose

to embrace the irrationality of their atheism had to find a way to live with

absolutes even though they believed such absolutes were not real.

In today’s post, I will be

summarizing Francis Schaeffer’s discussion on mysticism as it affected music

and art. Recall that mysticism is the third level below the line of despair.

The line of despair refers to the rejection of the existence of absolutes, such

as truth. This way of thinking is the natural byproduct of atheism. If the universe

is not God’s universe, but instead it is random material happenings, then there

can be no absolutes. Truth would be relative, right and wrong would be concepts

of nonsense, and all existence would be without meaning and purpose. Many

people bought into this, but it proved impossible to live out. As humans made

in the image of God, we live according to absolutes, we cannot separate ourselves

from them, and we intrinsically know that everything has meaning and purpose.

We know things are not random. Our very lives depend on the universe being

stable and predictable rather than random and chaotic. So those who still chose

to embrace the irrationality of their atheism had to find a way to live with

absolutes even though they believed such absolutes were not real.

Nihilism gave way to dichotomy,

which allowed people to pick whatever truth they wanted to believe in, while at

the same time understanding that it is nothing more than a preference based on

one’s leap of faith. Well, this dichotomy was not good enough for some, and so mysticism

was the next result. Mysticism was this idea that there is some sort of

absolute, but it is unknowable. All attempts to define and explain it are

inadequate and therefore are equally valid expressions of the truth. Mysticism

became necessary because most people could not deal with the idea of reality

being meaningless.

By this point of reading my posts, I

hope you can see that each major thinker that has been introduced has a

different explanation of what this mystical absolute is. It is no different

with music. Schaeffer focuses in on John Cage (1912-1992). He was so committed

to the idea that the universe is random, that he saw that randomness as the

mystical absolute. He did whatever he could to make his music random too. He

would compose his music after flipping coins thousands of times. Eventually the

methods became more sophisticated than this, but the result was the same –

music that made little sense to the ears. Cage believed that the “truth” of

chance can best be communicated through chance methods coming forth in his

music. Well, sometimes when his music was played, rather than offering applause,

the audience hissed and booed. Why? It is rather simple. In our heart of

hearts, we know that the universe is not meaningless and it is not random. It

is designed with intelligent purpose. We were designed with intelligent

purpose, and given that we ourselves are designed along with everything else in

nature, anything we create must be intelligently designed too. Cage’s randomly designed

music was not pleasing to our ears. If chance is the true mystical reality,

then chance should be able to communicate to us, but it cannot. Why? Because

the ultimate reality is not chance! The fact that his music was aesthetically

worthless should have caused him to reject his own presuppositions of

randomness, but instead he pressed on and continued to produce utter nonsense.

Consider this one more example of an atheist claiming to believe the evidence,

but then ignores the largest pieces of evidence that stare him right in the

face.

By this point of reading my posts, I

hope you can see that each major thinker that has been introduced has a

different explanation of what this mystical absolute is. It is no different

with music. Schaeffer focuses in on John Cage (1912-1992). He was so committed

to the idea that the universe is random, that he saw that randomness as the

mystical absolute. He did whatever he could to make his music random too. He

would compose his music after flipping coins thousands of times. Eventually the

methods became more sophisticated than this, but the result was the same –

music that made little sense to the ears. Cage believed that the “truth” of

chance can best be communicated through chance methods coming forth in his

music. Well, sometimes when his music was played, rather than offering applause,

the audience hissed and booed. Why? It is rather simple. In our heart of

hearts, we know that the universe is not meaningless and it is not random. It

is designed with intelligent purpose. We were designed with intelligent

purpose, and given that we ourselves are designed along with everything else in

nature, anything we create must be intelligently designed too. Cage’s randomly designed

music was not pleasing to our ears. If chance is the true mystical reality,

then chance should be able to communicate to us, but it cannot. Why? Because

the ultimate reality is not chance! The fact that his music was aesthetically

worthless should have caused him to reject his own presuppositions of

randomness, but instead he pressed on and continued to produce utter nonsense.

Consider this one more example of an atheist claiming to believe the evidence,

but then ignores the largest pieces of evidence that stare him right in the

face. An interesting point to note about

Cage is that like all other atheists that claimed there are no absolutes, he could not apply this belief consistently. To his credit, he did apply his philosophy

to his craft of music. In that sense, he was consistent. However, he eventually

became a mushroom enthusiast. He would wander the forest and study mushrooms

diligently to where he became a very well informed amateur mycologist. He had a

large library just on mushrooms, and knew that many were deadly and poisonous. He

is quoted as saying, “I became aware that if I approached mushrooms in the

spirit of my chance operations, I would die shortly. So I decided that I would

not approach them in this way.” In other words, he could not apply what he

believed to be the truth of the universe to the simple hobby of picking

mushrooms. If he picked mushrooms randomly, he would be dead in a few days. With

his life on the line, he practiced mycology as though there were absolutes,

meaning is real, and intelligent care must be taken with each mushroom. This is

just one more proof that that Cage’s atheistic assumptions were wrong. The fact

that people booed his music because it was random, and the fact that he would

not randomly pick mushrooms because his life was at stake both demonstrate the

impossibility of living according to his assumptions. These were two screaming

realities that should have caused him to reject his folly, and seek the real

truth.

An interesting point to note about

Cage is that like all other atheists that claimed there are no absolutes, he could not apply this belief consistently. To his credit, he did apply his philosophy

to his craft of music. In that sense, he was consistent. However, he eventually

became a mushroom enthusiast. He would wander the forest and study mushrooms

diligently to where he became a very well informed amateur mycologist. He had a

large library just on mushrooms, and knew that many were deadly and poisonous. He

is quoted as saying, “I became aware that if I approached mushrooms in the

spirit of my chance operations, I would die shortly. So I decided that I would

not approach them in this way.” In other words, he could not apply what he

believed to be the truth of the universe to the simple hobby of picking

mushrooms. If he picked mushrooms randomly, he would be dead in a few days. With

his life on the line, he practiced mycology as though there were absolutes,

meaning is real, and intelligent care must be taken with each mushroom. This is

just one more proof that that Cage’s atheistic assumptions were wrong. The fact

that people booed his music because it was random, and the fact that he would

not randomly pick mushrooms because his life was at stake both demonstrate the

impossibility of living according to his assumptions. These were two screaming

realities that should have caused him to reject his folly, and seek the real

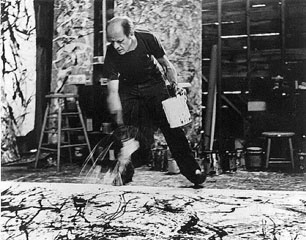

truth. The painter Jackson Pollock

(1912-1956) also decided to use the “mystical absolute” of chance to direct his

painting. He is famous for laying canvases on the floor, and allowing paint to

randomly drip on them. Because of the atheistic philosophical message that lied

behind the ugly drip paintings, many saw this as brilliant. But at the end of

the day, very few people’s eyes actually crave to stare at random drops of

paint on a canvas. When artists buy into thought below the line of despair,

this is the type of thing that happens. The artists of the Renaissance painted

their worldview, which was fairly biblical. Painting, sculpture, and

architecture were ways to communicate the biblical stories and truth to the

masses. Well, these atheist artists that live below the line of despair choose

to communicate their belief and story with these bizarre paintings that are

sore on the eyes.

The painter Jackson Pollock

(1912-1956) also decided to use the “mystical absolute” of chance to direct his

painting. He is famous for laying canvases on the floor, and allowing paint to

randomly drip on them. Because of the atheistic philosophical message that lied

behind the ugly drip paintings, many saw this as brilliant. But at the end of

the day, very few people’s eyes actually crave to stare at random drops of

paint on a canvas. When artists buy into thought below the line of despair,

this is the type of thing that happens. The artists of the Renaissance painted

their worldview, which was fairly biblical. Painting, sculpture, and

architecture were ways to communicate the biblical stories and truth to the

masses. Well, these atheist artists that live below the line of despair choose

to communicate their belief and story with these bizarre paintings that are

sore on the eyes. Perhaps it is noteworthy that we can

stare for hours at paintings that reflect the biblical worldview. We can appreciate

their beauty and we intrinsically appreciate the order and design behind them.

Yet, when it comes to the “religious/philosophical” message of the atheist

artists, we can only bare to look for a short time. We cannot appreciate

disjointed chaotic expressions. Maybe this is simply one more reality screaming

in the face of such artists, and yet it is a reality they choose to suppress.

We are what the Bible says we are, and this is why we appreciate art and music

consistent with the biblical worldview of order and design. If we were really

products of chance, then we should be able to enjoy these “chance-based”

artistic productions. Since we are made in the image of God, we cannot enjoy

these things. Instead, we can only mourn for the tortured souls that put such

chaos on canvas. Sadly, Jackson Pollock became entirely hopeless after he

exhausted what could be done in art with his “chance” method. In 1956, he

committed suicide. This is the frustration that comes from trying to

consistently live as though the Bible is not true. Most forms of mysticism falsely

help people avoid the despair, but Pollock was able to find no such relief.

Perhaps it is noteworthy that we can

stare for hours at paintings that reflect the biblical worldview. We can appreciate

their beauty and we intrinsically appreciate the order and design behind them.

Yet, when it comes to the “religious/philosophical” message of the atheist

artists, we can only bare to look for a short time. We cannot appreciate

disjointed chaotic expressions. Maybe this is simply one more reality screaming

in the face of such artists, and yet it is a reality they choose to suppress.

We are what the Bible says we are, and this is why we appreciate art and music

consistent with the biblical worldview of order and design. If we were really

products of chance, then we should be able to enjoy these “chance-based”

artistic productions. Since we are made in the image of God, we cannot enjoy

these things. Instead, we can only mourn for the tortured souls that put such

chaos on canvas. Sadly, Jackson Pollock became entirely hopeless after he

exhausted what could be done in art with his “chance” method. In 1956, he

committed suicide. This is the frustration that comes from trying to

consistently live as though the Bible is not true. Most forms of mysticism falsely

help people avoid the despair, but Pollock was able to find no such relief.  In terms of literature, we can

return to Henry Miller (1891-1980) of whom I wrote of before. He originally intended

to use his gift of writing to destroying meaning in general, especially with

regard to sex. So he wrote extremely dirty things meant to defile the mind and trivialize

meaning where it mattered greatly. Yet, later in life, he changed his position.

In fact, if one were not a careful reader, they might assume he became a

Christian. He started using Christian words, biblical imagery, and he certainly

became focused on spiritual matters. He even quoted Scripture. Like Salvador

Dali, he saw spiritual significance in the dematerialization of matter into

energy. He began to believe the ultimate reality was certainly spiritual, and that

meaning does in fact exist. However, his faith was in pantheism. He believed the

universe itself is the divine reality, and we are just part of it. Individual

man does not matter, but we are just one small part of the whole. As I said in

previous posts, this is not too far off from Eastern Hinduism. Francsis

Schaeffer sums up Miller by writing, “He is doing the same as Salvador Dali and

the new theologians—namely,

using Christians symbols to give an illusion of meaning to an impersonal world

which has no real place for man.”

In terms of literature, we can

return to Henry Miller (1891-1980) of whom I wrote of before. He originally intended

to use his gift of writing to destroying meaning in general, especially with

regard to sex. So he wrote extremely dirty things meant to defile the mind and trivialize

meaning where it mattered greatly. Yet, later in life, he changed his position.

In fact, if one were not a careful reader, they might assume he became a

Christian. He started using Christian words, biblical imagery, and he certainly

became focused on spiritual matters. He even quoted Scripture. Like Salvador

Dali, he saw spiritual significance in the dematerialization of matter into

energy. He began to believe the ultimate reality was certainly spiritual, and that

meaning does in fact exist. However, his faith was in pantheism. He believed the

universe itself is the divine reality, and we are just part of it. Individual

man does not matter, but we are just one small part of the whole. As I said in

previous posts, this is not too far off from Eastern Hinduism. Francsis

Schaeffer sums up Miller by writing, “He is doing the same as Salvador Dali and

the new theologians—namely,

using Christians symbols to give an illusion of meaning to an impersonal world

which has no real place for man.”

Sadly, this mysticism did not spare

theology. Just like dichotomy infiltrated theology after it captured the other

disciplines, so too did mysticism. Next time I will focus on what Schaeffer

calls the new theology.

No comments:

Post a Comment